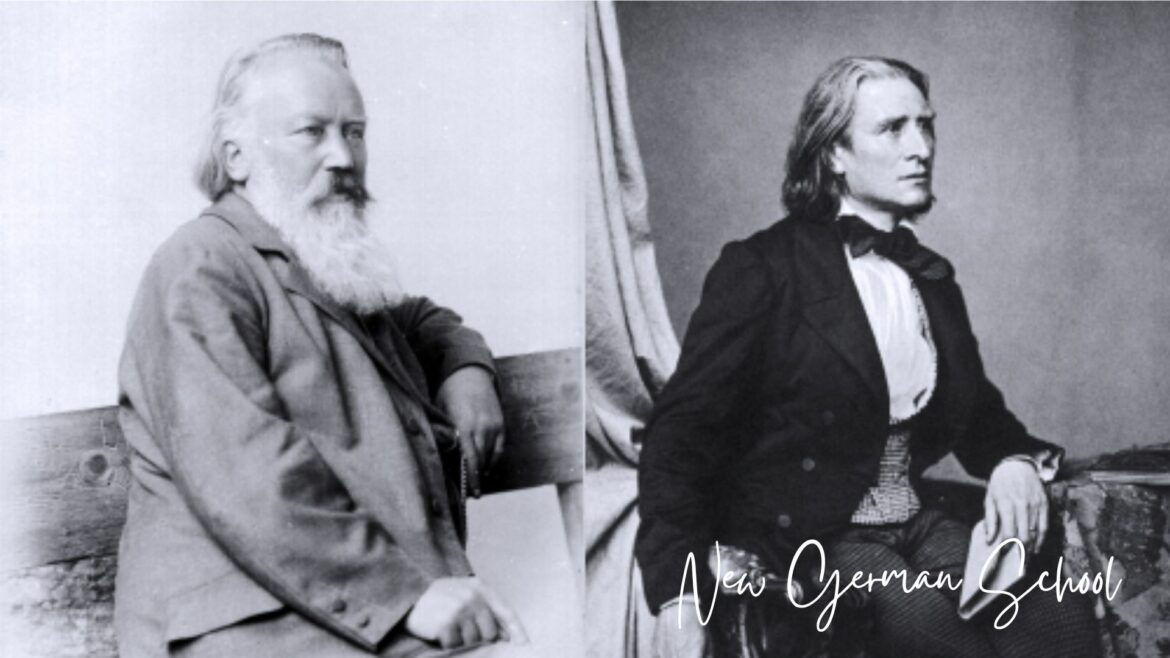

在十九世紀的德國音樂史中,布拉姆斯常被放在一個相對「保守」的位置,與李斯特、華格納等人所代表的新德國樂派形成對比。這樣的分類在音樂史書寫中確實存在,也方便教學與理解,但其實很容易讓人誤會布拉姆斯的創作態度,甚至低估了他在音樂語言上的前瞻性。

這兩種音樂美學的衝突在19世紀後半的音樂界引發了廣泛的討論,被稱為「音樂之戰」。新德國學派主張音樂應該與生活、文學和視覺藝術更緊密地結合,而布拉姆斯則認為音樂應該是自我表現的純粹藝術。

為什麼布拉姆斯常被歸類為「保守派」

布拉姆斯之所以被視為保守派,主要來自他對古典音樂形式的高度重視。他持續使用奏鳴曲式、變奏曲、交響曲等十八世紀以來已經成熟的架構,並公開表達對某些「過度追求效果」的新音樂的不安。相較之下,李斯特與華格納則積極嘗試新的形式與表現方式,這種對比很容易被理解為「傳統對上前衛」。

然而,這樣的二分法其實是後人整理歷史時才逐漸定型的結果。對十九世紀中葉的作曲家而言,他們並不是站在某個既定陣營中,而是在回應一個共同的問題:在貝多芬之後,音樂還能如何繼續發展。

十九世紀德國音樂正在面對的轉折點

新德國學派的起源可以追溯到19世紀中葉,該派別的主要成員包括華格納和李斯特。他們的音樂創作靈感來自貝多芬的作品,將他視為音樂創新的偶像,貝多芬把交響曲與奏鳴曲的表現力推向前所未有的高度。十九世紀中葉的德國音樂界,正是在這種「傳統已臻成熟」的狀態下,開始出現方向上的分歧。

一部分作曲家選擇向外尋找突破口,將音樂與文學、哲學、戲劇結合;另一部分則選擇向內深化,在既有形式中發掘新的結構可能性。這並不是誰比較勇敢或保守的差別,而是對音樂本質理解的不同。

新德國樂派的核心想法與創作方向

音樂與文學、戲劇之間的連結

後來被稱為「新德國樂派」的一群作曲家,普遍相信音樂可以承載具體的思想與敘事內容。他們並不滿足於抽象的聲音結構,而是希望音樂能與詩歌、神話或哲學概念產生更直接的連結,這種創作觀點,促成了所謂「標題音樂」的發展。

標題音樂

標題音樂,一種音樂形式,音樂內容基於一個故事、場景或想法。新德國學派的作曲家將這種方法用於推進音樂的創新,他們將敘事元素融入音樂作品中,使聽眾能更深入地理解和體驗音樂。在這種音樂風格中,作曲家通常會將音樂與一個非音樂的主題連結起來,如一首詩、一段敘述或一幅畫。

例如:

- 以詩作為靈感:李斯特的許多交響詩都是以詩作為靈感來創作的。例如,他的《先知鳥》是受到維克多·雨果的同名詩句的啟發。

- 以畫面作為靈感:有些作曲家會選擇一個或多個視覺影像作為創作靈感,並試圖透過音樂來描繪這些畫面。例如,華格納的歌劇《尼伯龍根的指環》中的音樂就是在描繪劇中的情節和角色。

- 以概念或想法作為靈感:並不直接描述一個具體的故事或畫面,而是嘗試表達一種概念或情感。例如,李斯特的交響詩《悲慘世界》就是試圖透過音樂來描繪人類的悲慘處境。

音樂可能與一個非音樂主題有關,但理解和欣賞這種音樂並不需要聽眾對該主題有深入的理解。作曲家通常會透過他們的音樂來傳達與主題相關的情感和氛圍。

李斯特與華格納代表的創作

李斯特所發展的交響詩,是新德國樂派最具代表性的形式之一。這類作品通常以文學或哲學概念為出發點,透過音樂描寫抽象情感或思想。例如《在山上的聽覺》,靈感來自雨果的詩作,音樂中對比自然的崇高與人類內心的痛苦,並非敘事性的描寫,而是一種情感與觀念的轉譯。

華格納則將這種思維推向歌劇領域,他強調音樂、戲劇與舞台的整體性,透過反覆出現的主導動機來連結角色、情節與思想,使音樂成為敘事的一部分,而非單純的伴奏。

布拉姆斯對新德國樂派的看法

限制了對音樂的想像

布拉姆斯對標題音樂持有批判的態度。他認為當音樂被緊緊綁定於一個特定的故事、圖像或概念時,表現力和創新性就會受到限制。對他來說,音樂的真正力量在於能夠喚起聽者心中各種各樣的情感,而這些情感與想像並不需要直接地與作曲家的原始靈感相對應。

因此,他認為標題音樂以某種方式限制了聽者對音樂的個人詮釋,從而降低了音樂的藝術價值。

「進步」與「保守」之爭

在當時的文化氛圍下,這些美學差異逐漸被放大成公開對立。布拉姆斯與友人曾發表聲明,批評新派音樂過度追求效果;而新德國樂派的支持者,則反過來指責傳統派缺乏進取精神。媒體與評論的推波助瀾,使這場討論逐漸從創作理念轉變為立場之爭。

隨著時間推移,「進步」與「保守」成為簡化理解的標籤,但也正是在這樣的簡化中,許多細節與灰色地帶被忽略了。

進入二十世紀後,作曲家與學者才開始以不同角度重新評價布拉姆斯。勳伯格曾指出,布拉姆斯在動機發展與結構思維上的創新,其實為現代音樂鋪路。這種重新理解提醒我們,創新並不一定表現在形式的顛覆上,也可能存在於對既有語言的深化與重組。

想更了解布拉姆斯的鋼琴作品與生平嗎?歡迎閱讀:布拉姆斯的音樂生涯:揭秘他的奏鳴曲與狂想曲之藝術精髓 | JOHANNES BRAHMS